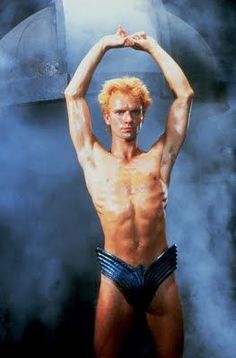

I just finished re-reading Dune. It's been at least 30 years since I last read it, and I really didn't remember much about it. I actually remembered more of the movie, even though I don't think I ever saw the whole thing. So, during this read, I always pictured Paul as "that guy from Blue Velvet"; and I (incorrectly) remembered Sting as Baron Harkonnen's evil advisor, Piter De Vries. In all of the scenes where Piter is plotting with the Baron, I was imagining Sting standing around in his crazy space speedo when I should have been picturing Brad Dourif (aka Grima Wormtounge).

I just finished re-reading Dune. It's been at least 30 years since I last read it, and I really didn't remember much about it. I actually remembered more of the movie, even though I don't think I ever saw the whole thing. So, during this read, I always pictured Paul as "that guy from Blue Velvet"; and I (incorrectly) remembered Sting as Baron Harkonnen's evil advisor, Piter De Vries. In all of the scenes where Piter is plotting with the Baron, I was imagining Sting standing around in his crazy space speedo when I should have been picturing Brad Dourif (aka Grima Wormtounge).

Oh well.

The book is both better and worse than I remember. The concept, the universe, the cultures, the religious mysticism, the vastness of the details - all better than I remembered. Big points for all that.

SPOLIERS!

The story moves along quickly, at first - pre-teen (?) boy figures out that he's the chosen one; there's an assassination, chaos, a big escape. And then it bogs down for a load of political intrigue between a huge cast of characters who don't really amount to much in the end. Paul learns in the very first chapter that he is going to be the messiah. And once his father is dead and he's head of the family (no regents in this kingdom), everybody else figures it out too. Without much effort, he becomes the leader, makes all the decisions, plots all the strategy - he can the future after all - and all other people are reduced to being his lieutenants or his ineffectual enemies.

It gets psychological, philosophical, and then psychedelic when he goes into the desert, takes his drugs, trips balls and sees the universe. He takes a ride on a giant worm. He's a haughty dick to everyone. There's a brief fight where a ruthless and corrupt imperial empire seeks to commit genocide against Paul and his space-Arab followers and is instead defeated by a sandstorm. There's a knife fight where the ending is never in doubt. And then the book ends, unsatisfyingly (despite having 10% of the pages left unturned - huge appendices, giant glossary). Literally the last paragraph of the story is Paul's mother telling Paul's girlfriend that even though she'll never be his wife, at least she'll be his concubine! Huzzah!

Women do not fare well in the world of Dune.

But what really bugged me was the clunky and flabby writing:

He held himself poised in the awareness, seeing time stretch out in its weird dimension, delicately balanced yet whirling, narrow yet spread like a net gathering countless worlds and forces, a tightwire that he must walk, yet a teeter-totter on which he balanced.

Ummm. OK?

And even though it logically makes no sense (it's not supposed to, I know - mystical), the flow of the words is reasonable, until that rickety "teeter-totter" shows up with its thorny cluster of T's and whimsical playground connotations. Was 'fulcrum' too fancy? Was "knife-edge" too appropriate in a story where everyone carries a knife on his hip? In the weird whirling narrow world of wires to be walked, is he aware of ... the teeter-totter?

And there's the dialogue. So much exposition. So many declarative sentences. Half of the people speak in the traditional stilted Ye Olde English of fantasy books, with Arabic and pseudo-Arabic words to spice things up.

Paul glanced to one of his Fedaykin lieutenants, said: “Korba, how came they to have weapons?”

"how came they to have..." sounds like a translation of a translation.

And the thoughts. Oh my, the thoughts. Half the main characters are experts at various mystical mental disciplines which give them deep insights into - and influence over - other people. So Herbert needed a way to integrate their internal dialogue into the text. And he did it by making their inner dialogue explicit, with italics:

Otheym pressed palms together, said: “I have brought Chani.” He bowed, retreated through the hangings.

And Jessica thought: How do I tell Chani?

“How is my grandson?” Jessica asked.

So it’s to be the ritual greeting, Chani thought, and her fears returned. Where is Muad’Dib? Why isn’t he here to greet me?

“He is healthy and happy, my mother,” Chani said. “I left him with Alia in the care of Harah.”

My mother, Jessica thought. Yes, she has the right to call me that in the formal greeting. She has given me a grandson.

“I hear a gift of cloth has been sent from Coanua sietch,” Jessica said.

“It is lovely cloth,” Chani said.

“Does Alia send a message?”

Their thoughts become asides for the characters to mock-whisper to the audience. So much talking. So much talk-thinking. So much pointless pretending the author hasn't already told us what's going to happen.

But, still, it's one of the most engrossing books I've read in a long time. Despite the clunky dialogue and the wooden characters and the unsatisfying ending, the world is so cool. The detail that Herbert put into it kept me hooked - I wanted to see more of them interacting with the desert, with the worms, with the 'spice'.

I'm sure I read the first sequel, but I don't remember any of it now. Maybe I should give it a try.